Adinkra in Ntonso-Ashanti, Ghana

|

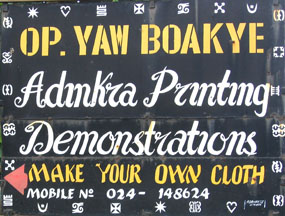

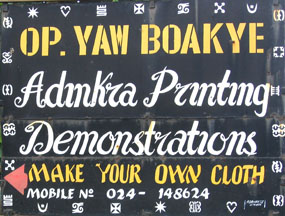

Adinkra cloth was originally only used as a mourning cloth. Today

it is also worn on other special occasions. The Boakye family demonstrates, teaches, and sells

Adinkra cloth in Ntonso. For a

demonstration, to buy Adinkra, to arrange for a class, or for more information, please

contact Peter Boakye in Ntonso-Ashanti, Ghana, West Africa. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ADINKRA ADURO MEDIUM: To make adinkra aduro medium (colorant), the bark

and roots of the Badie (Adansonia digitata) tree are harvested, the outer

layer is cut away, then the inner bark is broken into pieces and soaked in

water for 24 hours. It is then pounded for about 3 hours in a wooden mortar,

boiled for several hours in water over a wood fire, strained

through a plastic window screen, then boiled for 4 more hours. |

|

|

|

|

| CALABASH STAMPS: The inside of a dry, thick-skinned calabash

is covered with shea butter for a year to slightly soften it. Then Paul Nyamaah Boakye (telephone: 024345516 and

0243167605) cuts off a piece with a knife, scrapes the outer skin with a knife, draws the pattern

onto it with a pencil, then carves away the negative space with a gouge. Paul carves

more than 70 different symbols, each of which represents a proverb, belief,

or philosophy. |

|

|

|

|

| ADINKRA CLOTH PRINTING: Wooden planks resting on blocks

were covered with a 1" thick piece of foam rubber. Several symbols (which have

specific meanings) were chosen from an Adinkra chart, then the late Gabriel Boayke selected the stamps and

Anthony Boakye decided their placement on the cloth. After the starched shedder cotton fabric

(with a luster finish) was folded and laid on the foam rubber,

small nails were driven through the edges of the cloth with a rock.

Rocks were also placed along the edges of the cloth to keep it in place. A

comb (whose tangs were wrapped with nylon cord to help pick up the colorant) was

dipped into the adinra duro, then pulled across the cloth freehand to delineate

the sections to be printed. Although it requires practice and concentration,

expert printers are able to talk on a cell phone and converse with

onlookers while printing. |

|

|

|

|

| Following tradition, Anthony filled each section with

the same design. Before the section was actually printed, he figured out the placement by dry stamping

over the cloth. The stamp was then dipped into the adinkra duro and then the excess

was shaken off before bringing the stamp to the cloth. |

|

|

|

| One edge of the loaded curved stamp was placed onto the

cloth, it was rocked across to the other edge, then it was lifted and dipped

into the colorant once again to repeat the procedure. |

|

|

|

|

| Black cloth dye is prepared by soaking

Kuntunkuni (Bobax brevicuspe) bark and roots in a 50 gallon drum of water for

a few days, then boiling them over a wood fire, then beating the bark with a pipe,

then boiling them again until the liquid is very black. |

|

|

|

| Faded cloth that needs to be refreshed along

with new cloths are dipped several times into the powerful dye, then left outside

to dry. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SCREEN PRINTED ADINKRA CLOTH: Instead being decorated with Adinkra stamps,

some cloth is screen printed in Ntonso with

images adapted from traditional Adinkra stamps. They are drawn by hand or on a

computer, transferred to a screen at a shop, then printed on a

foam rubber covered surface with water-based fabric paint. The screens are

cleaned with water after each use and reused many times. Here we see Kitiwa or Junior

(Opanin Yaw Boakye Junior) screen printing onto cotton fabric while kente strips are

woven in the background. |

A short version of

The Twenty-first Century Voices of the Ashanti Adinkra and Kente Cloths of Ghana paper

that I presented at the 2012 Textile Society of America Thirteenth Biennial Symposium, Textiles and Politics,

is included in the Proceedings as a pdf.

Links:

Ashanti Kente Weaving in Bonwire, Ghana

Ashanti Kente Weaving in Adawomase, Ghana

Ewe Kente Cloth Weaving in Denu, Ghana

Glass Bead Making in Odumase Krobo, Ghana

Ashanti Glass Bead Making in Daabaa, Ghana

Lost Wax Casting in Krofofrom, Ghana

Painting and Baskets of Sirigu, Ghana

Ga Coffins in Teshie, Ghana

THREAD, Inc. Organization

More Links:

Papermaking in Kurotani, Japan

Katazome (stencil dying) in Kyoto, Japan

Shibori in Kyoto, Japan

Batik of Java and Bali, Indonesia

Ikat Weaving in Bali

Printing in China

Batik in Cameroon

Backstrap Woven Ikat in Mexico

Footloomed Woven Ikat in Mexico

Web page, photographs, and text by Carol Ventura in 2008 & 2009.

Please look at Carol's home page to see more about crafts around the world.

|